Early Oscar buzz surrounds new film based on Auburn University history professor's book on Neil Armstrong

Article body

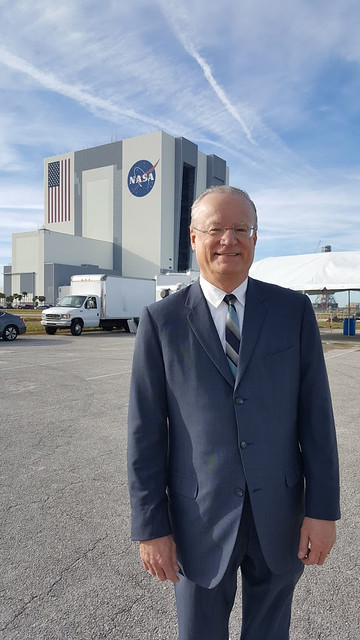

It was almost 50 years ago that astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins first journeyed to the Moon. Armstrong was the first person to ever step foot on the Moon – and that fact serves as the title of Auburn University History Professor (Emeritus) James R. Hansen’s book First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong (Simon & Schuster), and the new movie based on it, “First Man.”

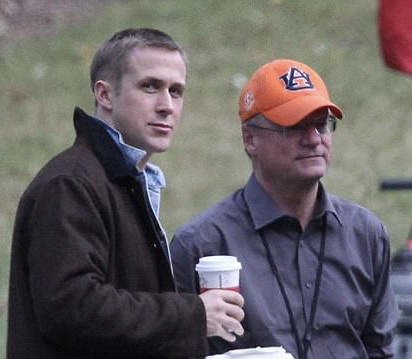

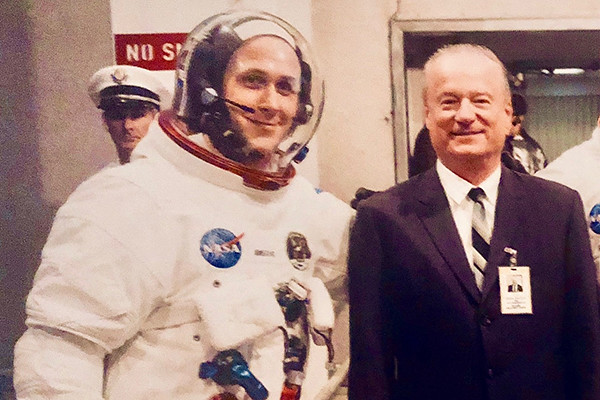

The film is receiving early Oscar buzz and stars Ryan Gosling (“The Notebook”), Claire Foy (“The Crown”), and Kyle Chandler (“Friday Night Lights”), and is directed by Academy Award winner Damien Chazelle (“La La Land”). The “First Man” movie script was written by another Oscar winner, Josh Singer (“Spotlight”), and is derived from Hansen’s book, which chronicles the life of Armstrong both before and after landing on the Moon in 1969. Hansen is a co-producer of the film and spent a lot of time on the set in Atlanta getting to know the actors and giving advice about how best to portray Armstrong. But how did a history professor at Auburn University become a co-producer on a major Hollywood film? And how did Hansen become the biographer for Neil Armstrong, who is a notoriously private individual, in the first place?

First contact: How Hansen became the official biographer of Neil Armstrong

After receiving his Ph.D. from The Ohio State University in 1981, Hansen worked for NASA on a book project before coming to Auburn in 1986 where he taught aerospace history and the history of science and technology for 31 years. It was during a class that Hansen professed his ambition to write about Neil Armstrong.

“I first verbalized it in front of a graduate seminar in 1999. I had the students go around the room and talk about what they were interested in, and afterwards, they had asked me what I was doing, and wanting to do next, and I told them that I was interested in pursuing a book about Neil Armstrong, but I didn't think the chances were very good because Neil was so hard to get in touch with.”

When the astronauts returned to Earth, Armstrong was not receptive to the unceasing media attention he received. For over 30 years, Armstrong refrained from participating in the national and international spotlights, choosing instead to live on a farm in rural Ohio and hire someone to manage his mass volume of mail. With encouragement from his students, Hansen began to formulate a way to contact Armstrong.

“I got his post office box number in Lebanon, Ohio, which is a little town north of Cincinnati where Neil, for several years, had a farm and was teaching at the University of Cincinnati. He had hired a woman to triage his mail, and when my letter arrived at the post office box, she thought he should see it.”

To his surprise, Hansen received a response from Armstrong and shared it with his class.

“It was a very nice letter, but it was basically a polite ‘not at this time’. He was still busy with some of his corporate responsibilities. My students encouraged me not to give up, but I made it clear to them that Neil was not the kind of guy to keep bugging, because that was not going to work. I knew his birthday was coming up and I thought I’d send him a few of my books, just as a gift. Maybe that'll open the door, a little bit. Maybe it won't. If not, it'll just be neat to know that Neil Armstrong has some of my books."

A month passed until Hansen heard from Armstrong again.

“He wrote me back and thanked me for the gifts and said that he had read one of the books, cover to cover, and browsed the others. He basically just said, ‘Let's keep talking.’ That was a good sign.”

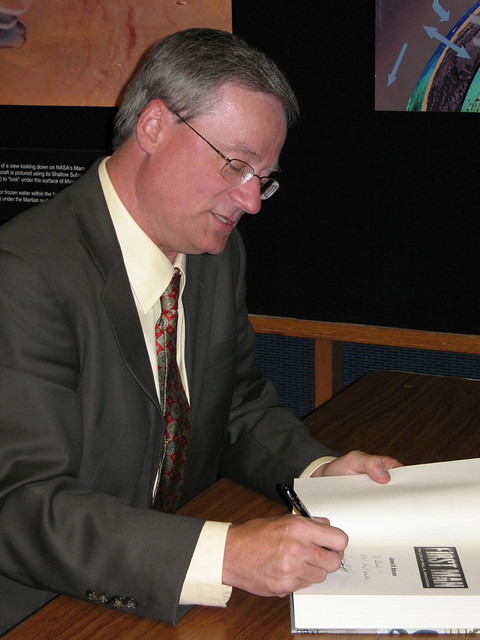

Armstrong eventually turned his life story over exclusively to Hansen. Presumably, Armstrong knew he was in good hands with Hansen’s wealth of experience and research. Hansen had written about aerospace history and the history of science and technology for 20 years by that point. He had published books and articles on a wide-variety of topics ranging from the early days of aviation, the first nuclear fusion reactors, and the moon landings, to the environmental history of golf courses. In 1995 the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) nominated Hansen's book Spaceflight Revolution for a Pulitzer Prize, the only time NASA ever made such a nomination. His scholarship had also been honored with the Robert H. Goddard Award from the National Space Club and certificates of distinction from the Air Force Historical Foundation. In addition to being an established and respected author, Hansen’s teaching and research had received numerous awards and accolades from the university. In 2005, he was inducted into the College of Liberal Arts' Academy of Teaching and Outstanding Scholars. Hansen also later became the Director of Auburn University Honors College (2006-12) and in the first four years he served as director, the total enrollment of the Honors College tripled.

In the years that proceeded those early attempts with Armstrong, communication between the two men became more frequent and Hansen said they maintained a friendly relationship, but that friendship was not the goal.

“When I was doing the interviews for the book, I wasn't there to become his friend. I was there to try to write a scholarly biography and I knew that I had to keep a certain emotional distance because there might be some things about his life that I would need to scrutinize quite closely. This was the remarkable thing about Neil – he never tried to control anything about the book, or what I said. He was there to answer my questions, and he was there to help me keep things technically accurate, but he didn't try to change any of my interpretations. He was just a resource for the book. After the book was done, the nicest compliment he gave me was, ‘Jim, you wrote exactly the book you told me you were going to write.’ For him, that was a big deal, because so many people in his life after Apollo 11 would say one thing and actually do another, try to manipulate things to their advantage. Neil just hated that. That's why he was quite reluctant to get involved in a lot of projects, because they just didn't turn out to be what he had been told they would be. Mine did.”

One giant leap: from professor to co-producer

Hansen and Armstrong, both from the Midwest, maintained a good partnership and had a great deal of respect for each other. When asked if he thought his book would turn into a movie when he was researching it, Hansen candidly answered, “I probably did.” Even though Armstrong didn’t want to be part of a movie deal, Armstrong did start to warm up to the idea of a movie being made based off Hansen’s book, and even met with actor/director Clint Eastwood to discuss a film project.

“Through my book agent, we heard from Hollywood that they were interested. Originally, it was Clint Eastwood. Clint Eastwood and Warner Bros.”

Hansen told Armstrong about it and both men and their wives were invited to Eastwood’s private golf club in Carmel, California.

“His golf course was up in the hills above Pebble Beach. He had us come out, and Neil, and I, and Clint played a round of golf, which was really cool for me.” (Hansen is a golf enthusiast and recently authored an award-winning book about golf course architect Robert Trent Jones, Sr.)

Eastwood decided not to pursue the film and gave up the rights Warner Bros had purchased. After that, Hansen found out that Universal Pictures was interested. The current screenplay was not yet written when Armstrong passed away on August 25, 2012, but Neil’s two sons and other members of his family have been consulted about the film.

The film is receiving a lot of attention and positive reviews. “It’s very different from what you’d expect. It’s a really interesting approach to the astronaut genre … it almost feels like cinéma vérité or dogma in the way he [Damien Chazelle] shoots his characters, but then it’s epic and gripping when it gets into the stratosphere," said Cameron Bailey, president of the Toronto Film Festival, where the film will compete for a major international award in early September.

Hansen said that while being a co-producer was stressful (long hours on set in Atlanta and learning how to navigate the film communications process), he is ultimately pleased with how the film turned out.

“It’s not what most people would expect; it’s not another version of ‘The Right Stuff’ or ‘Apollo 13.’ It’s an artistic interpretation of Neil’s life,” Hansen states. “I went to a private screening in L.A. and I kept expecting people to get up at some point in the film to go to the bathroom or get more popcorn, but no one did. Not one person!”

When asked if he thinks Armstrong would be pleased with the film, Hansen said, “I don’t think he would like any film where he was the star – he always made the point that the astronauts were at the top of a big pyramid of other people that played a major part in making the Moon landing possible. Neil was such a stickler for facts, I think even a documentary could be difficult for him. I believe he would find the interpretation very provocative. I think he would've been, and his boys have told us this, he would've been extremely impressed with the technical work behind the movie.”

The next space odyssey

Hansen is working on a new book, Dear Neil Armstrong: Letters to the First Man on the Moon, (W.W. Norton, 2019). For this book project, Hansen has reviewed some 90,000 letters written to Neil in the years from the Moon landing in 1969 to his death in 2012. “The letters to Neil range across a very broad spectrum. Thousands of them are letters and cards from children. Many of them ask for photographs or signed pictures. The letters come from all over the world. Some pretty crazy letters were written to Neil, too, by religious fanatics and people who believed in some conspiracy theory that the U.S. government faked the Moon landings. It is really interesting to see what society and culture projected onto to Neil, and just as interesting to see what Neil wrote back to everyone.”

Also on the horizon for Jim is a reality TV documentary series called “The Moon Rock Hunters.”

“Believe it or not, a lot of the Moon rocks brought back by the six Apollo lunar landings can’t be found, they’ve gone missing. Some have been stolen. The concept for this TV series, which I developed in association with Houston’s Robert Pearlman, the world’s foremost expert on space collectables, is to investigate the most interesting cases of the missing Moon rocks and recover as many of them as possible.”

Of the 270 Moon rocks brought back by Apollo 11 and Apollo 17—and later given to the States of the U.S, and to the nations of the world as part of a Goodwill Moon Rocks program started by the Nixon Administration—approximately 180 are unaccounted for. “Technically, no Moon rock has a monetary value, as none are legal to possess,” Hansen explains. “But if you go by the $50,800 in 1973 dollars per gram number that came out of a 2003 federal court case, that sets the value of a Moon rock at $300,000 per gram. Therefore, a Moon rock of any size on the black market is worth millions of dollars. We aren’t looking for the lost Moon rocks to make money, of course, but to give them back to whom they belong, primarily the American public and the legacy of Apollo.”

Related Media

Media interested in this story can contact Communications Director Preston Sparks at (334) 844-9999 or preston.sparks@auburn.edu.

The College of Liberal Arts is the intellectual heart of the university and one of the largest colleges on Auburn's campus. The College continues its long tradition of quality education, instruction, and outreach in a number of outstanding departments. The College of Liberal Arts is composed of the School of Communication and Journalism, the University College, and twelve departments which are divided into four academic areas: fine arts, humanities, communications, and social sciences. Our graduates hold a strong record of industry employment and/or acceptance into graduate schools and training programs, both here and abroad.